Hebraic Leadership Paradigms and Pauline Ecclesiology

A Theological Integration of Ephesians 4:11–12, the ascension gifts,

with the servant leadership of Bishop and Deacon

This article explores the structural and theological continuity between Hebraic leadership models and the Pauline doctrine of ministerial, ascension gifts articulated in Ephesians 4:11–12, with particular attention to the ecclesial servant positions of bishop (ἐπίσκοπος) and deacon (διάκονος) that Paul introduces to Timothy and Titus (1 Tim. 3:1-13; cf. Titus 1:5-9). It argues that Paul’s ecclesiology is not a drastic departure from Hebraic leadership paradigms, but a Christological fulfillment and ecclesial transformation of them. Drawing from Torah leadership structures, Second Temple Jewish institutional forms, and early apostolic church organization, this study demonstrates that Pauline ministry theology reflects a Hebraic framework of delegated authority, communal responsibility, service and spiritual formation. The article further proposes that the New Testament servant positions of bishop and deacon represent functional developments of Hebraic models of oversight and service, reconstituted in the light of Messiah Yeshua/Jesus, and the outpouring of the Spirit.

I. Introduction: Continuity Rather than Innovation

There is considerable confusion, conversation and argument regarding the ascension gifts (Eph. 4:10), or commonly, the five-fold ministry gifts, used interchangeably in this paper, and their function in contemporary congregational or denominational organization. Are the ascension gifts simply another set of titles to confer, or were they functional descriptors of the mission to “build up the body of Christ”[1] regarding those serving and laboring to bring us to maturity? As we will consider, the nature and purpose of the ascension gifts at times overlapped, but the authority of each gift resides in the message of Christ. It is clear that Paul anticipates the purpose of the gifts to be directly involved with preparing the saints for the “work of the ministry” (Eph. 4:12). We note that he does not directly link them to ministry itself, although they could be classified as ministry, but to the maturing or discipling of those having received the gospel of Messiah. How did Paul view the landscape of his Jewish upbringing and training to inform his presentation of the ascension gifts, and the roles of bishop and deacon?

Paul’s language in Ephesians 4:11–12 draws on the ancient image of a victorious king ascending in triumph, and distributing the spoils of war. By quoting Psalm 68 (Eph. 4:8), a psalm celebrating the Lord as a divine warrior who defeats his enemies, ascends his mountain, and receives tribute, Paul reframes the scene around the victory of Messiah. In this retelling, Christ not only ascends in victory, but also gives gifts to his people, echoing a practice among ancient Near-Eastern kings who shared plunder with key leaders after battle to ensure both economic stability of their kingdoms, and the military support necessary for defense and survival.

Abraham’s actions in Genesis 14 provide a biblical pattern that Paul may be alluding to in Ephesians 4. After defeating an alliance of four kings, Abraham behaves like an ancient Near-Eastern chieftain/king: he rescues captives, recovers goods, refuses personal enrichment, gives a tithe to Melchizedek, and ensures that his allies receive their rightful share of the spoils. It is this type of familiar victory‑distribution pattern that Paul applies to Christ’s ascension, quoting Psalm 68 to portray Yeshua/Jesus as the triumphant divine warrior who descends into conflict, conquers hostile powers, ascends in victory, and then distributes the benefits of that victory to his people. In place of material spoils of war, Christ gives the church empowered servants (apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors, and teachers) who function as the transformed spoils of his triumph over death and the grave (1 Cor. 15:54-57; cf. Rev. 1:18).

In this framework, rather than material goods, Christ distributes empowered people and ministries that strengthen and build up the saints “for the work of ministry” (Eph. 4:12). This comparison has long been widely recognized in scholarship. Paul’s intentional use of royal‑victory imagery to portray Christ’s triumph, and the generous outpouring of its benefits on the church, is both biblical and historic.

Modern ecclesiological thought often treats Pauline church structures as unique developments distinct from Israel’s leadership traditions. However, such a dichotomy is historically and theologically unsustainable. Paul, a Pharisee trained “at the feet of Gamaliel” (Acts 22:3), did not construct ecclesial models in a cultural or theological vacuum. His theology and leadership concepts are deeply rooted in Hebraic leadership frameworks, rabbinic forms of authority, and temple-centered patterns of service. In Paul’s faith and practice, he did not abandon his Jewish identity for one influenced by the Greco-Roman worldview. He lived his own rule for all churches articulated in 1 Corinthians 7:17-24, “So, brothers, in whatever condition each was called, there let him remain with God” (v.24). It would stand to reason that the social, cultural and religious forms of his youth would inform, to some degree, his ecclesial instruction.

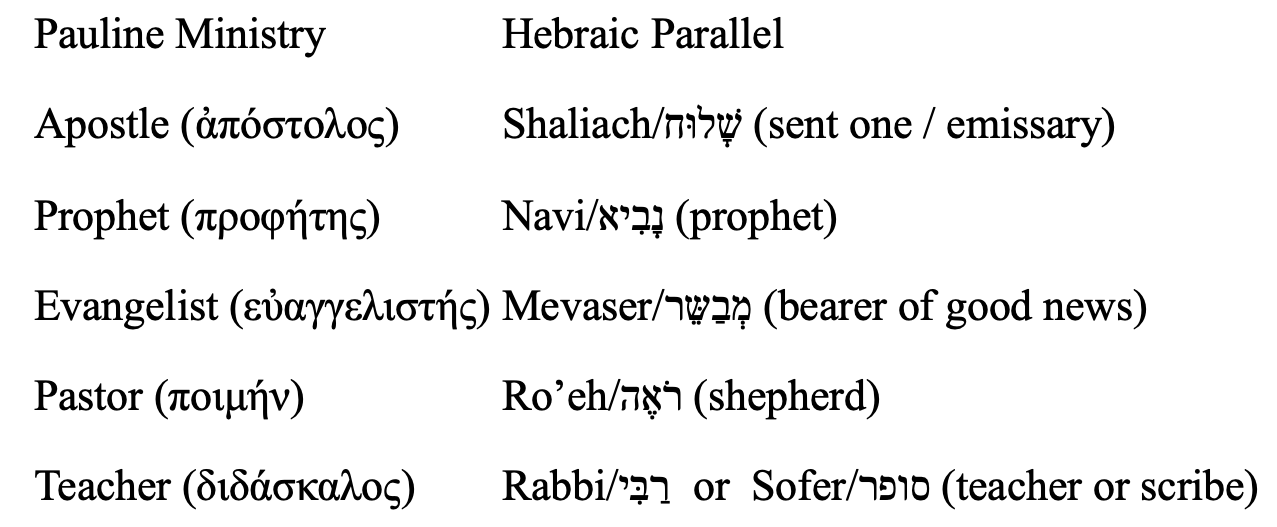

Ephesians 4:11–12 presents what is commonly termed the five-fold ministry: “And he gave some, apostles; and some, prophets; and some, evangelists; and some, pastors and teachers; For the perfecting of the saints, for the work of the ministry, for the edifying of the body of Christ.” This text reflects not just a charismatic diversity, but structural theology; a vision of ordered mature leadership functioning toward communal formation (oikodomē) rather than hierarchical domination. Paul’s intent was not a professionalizing of members of the churches, but a way of presenting Christ’s gifts as servant roles to his Bride. He is presenting structural theology rather than bureaucratic structure.

II. Hebraic Leadership Structures: Delegation, Function, and Covenant

A. Mosaic Delegation Model (Ex. 18; Num. 11)

Hebraic leadership does not begin with centralized or top-down control, but rather delegated authority. Jethro’s counsel to Moses (Ex. 18:17–26) establishes a graded leadership structure: leaders of thousands, hundreds, fifties, and tens. Authority is distributed, functional, and covenantal, not autocratic or solely charismatic.

Numbers 11 further grounds this model through the seventy elders who receive of the Spirit (ruach) resting upon Moses, demonstrating spiritual empowerment rather than political delegation. This forms a type of proto-ecclesiology: authority is derived, not self-generated; leadership is plural and working in concert with others, not monocratic; function precedes title; and service precedes status. We find in these principles direct parallels to Paul’s ministry theology.

B. Prophetic, Priestly, and Scribal Roles

Hebraic leadership is not monolithic, but vocationally diverse:

Priests (kohanim), anointed and hereditary: sacramental mediation.

Levites (leviim), hereditary: sacramental assistant.

Prophets (nevi’im); anointed: revelatory authority.

Scribes/Teachers (soferim / rabbanim), educated: instructional authority.

Elders (zekenim), age, reputation, character: communal governance.

This vocational plurality anticipates Paul’s ministry typology in Ephesians 4:11-12. The five-fold ascension gifts are not innovations, but Messianic reconfigurations of these roles within the Body of Messiah.

III. Ephesians 4:11–12 as Hebraic Ecclesiology

A. Functional Rather than Hierarchical Design

The language of Ephesians 4:11 emphasizes gifted function, not institutional rank. The gifts are given (edōken) by Messiah, not claimed by individuals. Their purpose is equipping (katartismos) and edifying (oikodomē), not control. While a formal recognition of these ministries may not have been practiced during different ages in Church history, their functional presence never ceased. The primary purpose of the ascension gifts is discipleship in broad application.

This reflects the logic of Hebraic leadership: which exists for covenantal and communal formation, not personal authority. The telos is maturity in the church: “the building up of the body” (oikodomē tou sōmatos); “the unity of the faith” (henótēta tēs písteōs); “mature manhood” (andra teleion). This is covenant anthropology, not institutional or organizational management.

B. Five-fold Gift Ministry and Hebraic Parallels

The apostle as shaliach (sent one) is particularly significant: in Jewish law, “the one sent is as the one who sends him,” שְׁלוּחוֹ שֶׁל אָדָם כְּמוֹתוֹ (BT Nedarim 72b; Kiddushin 41b). The one sent is permitted to act on behalf of the one sending to the extent of the authority granted them, grounding apostolic or five-fold ascension gift ministry in representational covenant theology, not personal charisma. The one sent would be received as the one sending (Matt. 10:40-42). While later rabbinic literature codifies this concept, the shaliach model does reflect earlier Second Temple legal customs already operative in Paul’s Jewish milieu. The shaliach model finds immediate relevance concerning the other ascension gifts, providing clear guidance as to essential function and the scope of each gift within a congregational setting.

IV. The Office of Bishop (ἐπίσκοπος) as Hebraic Oversight

A. Semantic and Functional Analysis

The term episkopos, meaning “overseer,” was a widely used Greek administrative title within the broader Greco-Roman world signifying an overseeing official or commissioner; but it functionally aligns with the Hebraic role of: פָּקִיד/Pakid (overseer/administrator); זָקֵן/Zaken (elder with communal authority); נָגִיד/Nagid (leader).

In Second Temple Judaism, oversight roles were institutional and communal, not sacerdotal in isolation. Paul’s bishop is not a monarchic ruler, but a guardian and steward of doctrine, ethics, and communal order (1 Tim. 3:1–7; Titus 1:7–9; cf. Eph. 4:14), in line with the Pakid, Zaken and Nagid of ancient Israel. Paul’s instruction to Timothy and Titus mirrors this: Torah guardianship; covenant fidelity; moral credibility; teaching responsibility; even the rendering of judicial verdicts (1 Cor. 5:12-6:8). The bishop is a doctrinal and ecclesial steward, not a corporate executive.

V. The Office of Deacon (διάκονος) as Sacred Service

The deacon (diakonos), while used in the Greco-Roman world as a messenger or agent of a higher authority, in Paul’s usage reflects the Hebraic theology of servant-leadership as a holy position. Hebraic parallels include Temple assistants; Levitical service roles; community servants/ministry, in Hebrew, מְשָׁרְתִים/mesharetim, or שָׁמַשׁ/shammash (meaning attendant, helper, servant-leader), which has become the usual translation of διάκονος/diakonos in modern Hebrew translations of the New Testament. German theologian and Hebraist Dr. Franz Delitzsch translates the first clause of 1 Timothy 3:8: וְכֵן גַּם־הַשַּׁמָּשִׁים יִהְיוּ יְשָׁרִים, “Deacons (הַשַּׁמָּשִׁים) likewise must be dignified” (Delitzsch’s translation was completed in 1877).

Acts 6 presents the deaconate as structurally necessary for justice, equity, and order as service to the saints, not simply arbiters for logistical or preparatory purposes. The Spirit-filled qualification (Acts 6:3; cf. 1 Tim. 3:8-13) reveals that service is a spiritual vocation, not administrative convenience. This suggests Hebraic theology where: service is not lesser authority; but rather, holy vocation expressed through humility.

VI. Integrated Model: Apostolic Structure as Messianic Fulfillment of Hebraic Order

Pauline ecclesiology expressed through the five-fold ascension gifts, as well as the bishop and deacon servant-leadership positions, represent a Messianic reconfiguration of Hebraic leadership. In Israel’s covenant community, kings, elders, prophets, priests, Levites, and later teachers (rabbi/scribe) fulfilled the primary social and spiritual leadership roles. Paul recasts this pattern, for the church where Christ is King, reimaged as the presbyter or bishop, the renewed prophetic ministry, the priesthood of all believers (Ro. 12:1; 15:15-16; 1 Pet. 2:9), the Spirit‑empowered service of the deacon (Acts 6:3), and the care of pastors and teachers.

Ephesians 4 specifically functions as an ecclesial foundation for the saints, not as a list of spiritual gifts to be self-applied. It establishes ordered diversity for communal formation, under the direct care of bishops and deacons.

VII. Implications for Contemporary Ecclesiology

Leadership is functional, not positional.

Authority is covenantal, not institutional.

Offices exist for formation, not administration.

Leadership structures serve to bring maturity, not control.

Service is theological, not logistical.

Modern church models that separate structure from theology and biblical history misunderstand Pauline intent. Ecclesial “offices” are not bureaucratic necessities, but spiritual architecture to build up the Body of Christ for the work of the Great Commission (Matt. 28:18-20).

VIII. Ecclesiological Formation and Care: Bishops, Deacons, and Five-fold Ministry

In his ecclesiological order, Paul did not establish bishops and deacons instead of or to replace the ascension gifts; they were established alongside them, because they serve different, but complementary purposes in the life and formation of the Body of Messiah. The five-fold ministry in Ephesians 4 describes gifted functions given by Christ for the spiritual formation and maturity of the Church “to the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ” (Eph. 4:13). The ascension gifts are Christological and missional. Bishops and deacons, on the other hand, represent structural ecclesial stability and communal order within local congregations “for if someone does not know how to manage his own household, how will he care for God’s church (1 Tim. 3:5; cf. Titus 1:5-9). One is primarily charismatic and formative in nature, while the other is pastoral, administrative, and protective in function, “For a bishop, as God’s steward, must be above reproach” (Titus 1:7).

The five-fold ministry is inherently mobile, translocal, and missionary. Apostles are sent ones who establish and strengthen communities. Prophets speak the word of the Lord for direction and correction. Evangelists carry the gospel outward. Shepherds nurture and tend people spiritually. Teachers ground communities in truth. These five-fold ascension gifts are not limited to one congregation, and they do not seem to be designed to manage daily community life. Their calling is to formation of the Body of Christ, not to govern its operations. They build spiritual foundations, awaken callings, shape identity, and mature believers, but they are not tasked with maintaining communal order, protecting doctrine at the local level, resolving disputes, administering care structures, or safeguarding congregational stability (Titus 1:9).

Bishops and deacons exist because the Church is not only a spiritual organism, it is also a living community that requires order, care, protection, accountability, and continuity. Without stable local leadership, congregations would remain spiritually dependent on remote influence, structurally and doctrinally fragile, and relationally vulnerable. Paul understood that spiritual gifting alone does not automatically produce healthy congregational life. People still need shepherding, oversight, discipline, organization, care systems, and moral guardianship. Simply, the Body of Christ needs stewardship. The Spirit empowers diverse gifts, but communities still require holy order and direction (1 Cor. 14:40).

Bishops were established to serve as guardians of doctrine, ethics, and communal health. Their role was to protect the flock from false teaching, spiritual abuse, division, and moral corruption, as Paul exhorted Timothy, “O Timothy, guard the deposit entrusted to you. Avoid the irreverent babble and contradictions of what is false called “knowledge” (1 Tim. 6:20). They provide continuity, stability, and pastoral care in a way that translocal ministers could not. They anchored the congregation so that it would not be dependent on traveling leaders for survival or spiritual coherence. Without bishops, congregations would remain perpetually immature, unstable, and externally dependent.

Deacons were established because spiritual life cannot flourish where practical needs are neglected (Acts 6:3). The early community recognized that spiritual vitality collapses when care, justice, and service structures break down (Acts 6:1). Deacons serve to ensure that charity (love) remains tangible, that care becomes organized, and that service becomes sustainable. They protect unity by preventing neglect, inequality, and burnout. They allow the community to function in compassion without chaos.

In other words, the five-fold ministry builds spiritual maturity, while bishops and deacons preserve spiritual stability. The five-fold ministry forms identity and calling around the Gospel; bishops and deacons protect community health, continuity, orthodoxy and orthopraxy. The five-fold ministry establishes vision and direction; bishops and deacons sustain daily life and order. One is primarily formational; the other is primarily foundational.

Paul’s direction in these matters reveals profound wisdom from the Lord, as revival without structure collapses, and structure without the Spirit becomes dead religion. The ascension gift ministry without bishops and deacons may lead to instability, fragmentation, personality-driven movements, and spiritual chaos. Bishops and deacons without the five-fold ministry can lead to stagnation, institutionalism, control systems, and spiritual dryness. The Church needs both movement and maintenance, both fire and formation, both charisma and order, both Spirit and structure. Properly administered by servant-leadership, the Church avoids extremes, and maintains a balanced, focused devotion to the Risen Messiah.

This is why Paul never presents these models as competing systems. He integrates them. Another way, the five-fold ministry shapes the Body’s growth and maturity, while bishops and deacons preserve the Body’s health and continuity. One moves the Church forward; the other keeps the Church anchored in Christ. One expands; the other stabilizes. One pioneers; the other preserves. At a deeper level, this reflects the Lord’s own nature. He is both dynamic and ordered, both living fire and holy structure, both movement and stability. Creation itself reflects this, as life grows within laws, power flows within form, and Spirit moves within order.

Paul’s vision was not a church of chaos or control, but a living covenant community where the Spirit moves freely within holy order. So Paul established bishops and deacons, not because the ascension gifts were insufficient, but because their ministry was not intended for the long-term daily needs and maintenance of Messianic community life. He was not building movements that would flare and fade; he was building communities that would endure, mature, and multiply across generations with proper care. In short, once again: the ascension gifts form the Body’s maturity. Bishops and deacons protect the Body’s health. Together, they create a Church that is alive, ordered, Spirit-filled, stable, and enduring. Organic, relational church life utilizes these gifts, even if they are not officially recognized. This is not bureaucracy; it is wisdom. This is not a new institutionalism; it is enduring, well-ordered stewardship. This is not curation, it is life. This is not a means of control; it is care. This is not a form of superior hierarchy; it is holy order among the royal priesthood. It is the design for a living community established not just for short-term growth, but for long-term endurance in Messiah.

IV. Conclusion

Paul’s teaching in Ephesians 4:11–12 is best understood not as a Greco-Roman organizational model, but as a Messianic reconstitution and renewal of Hebraic servant-leadership models. The “five-fold” ministries reflect vocational diversity rooted in Israel’s covenantal structures. The offices of bishop and deacon represent functional developments of Hebraic oversight and service, transformed through Christological authority and pneumatological empowerment.

Yet, it is important to distinguish between apostolic-era practice, in which ministry gifts and local offices functioned within living covenant communities under direct, but consensual apostolic moral oversight found in Jerusalem (Acts 15); and post-apostolic developments, even to their overt revival in the modern charismatic renewal, where these same functions were increasingly formalized in response to growth, persecution, necessary catechesis, and the need for institutional continuity across vast and diverse religious and geo-political landscapes. While it may seem that these natural, intentional, even necessary developments best preserve Paul’s leadership models, a noticeable consequence of this has been the establishment of an anointed leadership class and the laity, an initiated class and the uninitiated. A simple reading of Paul’s treatment in Ephesians 4:1-16 would recognize this as a distortion. This evaluation is not to diminish later developments, or to sanitize the often-messy apostolic landscape of the first-century, rather to appreciate the apostolic direction as an aspirational and corrective goal. In this light, ecclesial servant-leadership is neither hierarchical domination nor charismatic individualism, but community stewardship, a sacred trust ordered toward the formation of a mature, unified, and holy people of God, as Paul concludes:

“Rather, speaking the truth in love, we are to grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ, from whom the whole body, joined and held together by every joint with which it is equipped, when each part is working properly, makes the body grow so that it builds itself up in love” (Eph. 4:16).

In the service of Messiah and His Church,

Bishop Justin D. Elwell

Restoration Fellowship International

[1] ESV unless otherwise noted.